The Evidence

What Social Care Workers told us

Introduction

Below is a summary of the University of Strathclyde’s Scottish Centre for Employment (SCER) research findings[28] on how care workers and their employers understand the five dimensions of Fair Work. The following sections provide insights that connect with each of the five dimensions of fair work identified within the Fair Work Framework.

Evidence: security of income and employment

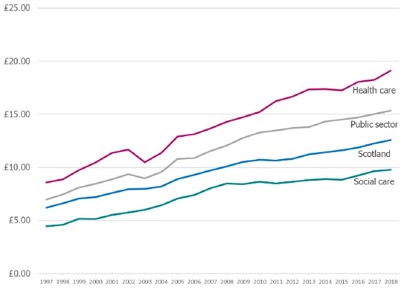

Predictable patterns and guaranteed hours of employment and income are fundamental to the provision of fair work. Low pay and income insecurity can lead to in-work poverty, child poverty and poverty beyond working life.[29] As Figure 3 indicates, median hourly pay in the social care sector lags equivalent pay in Scotland, in the public sector and in the health sector.

Figure 5: Median of hourly pay, (not adjusted for inflation)

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), ONS

In the SCER research, less than half of care workers reported always having sufficient hours of work or income to meet basic household requirements:

“I don’t think anyone’s fairly rewarded in care at the moment. The minimum wage seems like an excuse for people to pay the minimum wages. I don’t think it was designed for that. I know we don’t get the minimum wage here, but it is just a few pence more. I think people are worth more than that. But I’m not doing this for the money.”

“To me fair work in practice is about paying a fair salary for the type of job that we do and we are still (one) some of the poorest paid… people can go and earn quite literally ten pounds an hour stacking shelves… you’re not going to get the staff… give them fair salary because that’s the future.. It’s as simple as that.”

Care workers spoke about the need to work long hours to have any chance of making ends meet. They spoke of the need to take on full time hours and/or overtime to achieve a reasonable income. Leaders participating from the independent care sector spoke about the link between low pay, long working hours, stress and other health problems in the workforce:

“You need to work. You can’t afford to be unwell.”

“Workers have to accumulate hours to receive good enough pay [and this means] stress of long shifts with high levels of responsibility.”

Almost half (46%) of care employees viewed their pay as unfair compared with other jobs in their local labour market. They expressed frustration that their skilled work was not recognised by better pay. In addition to low pay, some reported not being fully reimbursed for travel costs, work-related phone use, internet use, uniforms, and meals with those they care for when out with them. National data also highlights that more than 16% of care workers deliver unpaid overtime weekly.

Source: The Labour Force Survey 2017, ONS

Leadership teams spoke about the need to establish a more level playing field in terms of pay, terms and conditions between directly-employed local government care workers and those employed in the third and independent sectors. Respondents leading independent firms responding to the SCER research spoke about the low hourly rates offered by local authorities for contracted-out care to independent providers compared to the higher rates for in-house provision.

Low pay is also often accompanied by relatively flat pay hierarchies. Some care workers raised concerns about the limited pay increases available for taking on more senior or team leader roles, particularly as payment of the Living Wage in Scotland has compressed pay differentials further:[30]

“I’m not taking on the extra responsibility of doing medications, going to people’s houses, assessing them. Getting involved with care plans. Social workers, doctors for nothing. There’s no way….Everybody needs to be decently paid.”

Managers agreed that more money needs to be made available to offer additional pay increments to employees adopting more senior roles, both to reflect their roles and responsibilities and to encourage progression and recruitment into these positions.

Low pay is not the only challenge for some care workers. While the care workers in the SCER survey did not express immediate worries about their own job security, almost three-quarters of care workers reported that at least some colleagues were worried about job security (more than 40% reported that most colleagues worried about job security). In part, these concerns arose from perceptions of the wider financial stability of the sector and the challenges of regular re-tendering:

“If we don’t get the contract awarded to us then everybody will be made redundant.”

“There is a system of tendering… people are aware of that, contracts come up for retendering, and it is unsettling. We could resolve it by not having short term tendering situations. Essentially, that would give people more security.”

However, although workers feel insecure, in reality some work many more hours than they want to,[31] suggesting that there are enough hours of work in the context of a growing need for social care services.

Source: The Labour Force Survey 2017, ONS

Some managers agreed that short-term commissioning practices contributed to job insecurity (and to problems of recruitment, turnover and retention). Some organisations reported that they had refused to engage in specific types of tendering because of the limited resources that could be provided for frontline staff under these tenders.

All organisations participating in the research delivered services across numerous local authority areas and therefore engaged in a range of local commissioning arrangements. There was an awareness of wide variations in commissioning with good examples built on collaborative principles, as well as more short-term, market-led forms of contracting-out. The former were seen as offering potential benefits in terms of security of funding for organisations and security of employment for staff.

While regular re-tendering appears to undermine employment security, staffing practices within care providers undermines the need for stable and predictable hours. In an environment which is challenging, where budgets are limited and there are frequent changes in the delivery care packages required, employers need to have a flexible labour supply which allows them to provide care at a sustainable cost. Zero hours and low hour contracts offer employers this flexibility, allowing employers to vary rotas and hours each week. Flexibility is predominantly employer-focused. Risks (in terms of hours available) are passed to the worker and managed through strict scheduling around users’ preferred hours. This means care workers often don’t know their rota, or how much work they have week to week. This makes planning their finances and their home life challenging. Although less than one in ten of the sample responding to the SCER survey were on non-fixed hours contracts, the statistic for the care sector as a whole is one in five.

Managers spoke about keeping a small number of workers in ‘relief’ banks of non-fixed hours’ staff. Managers also spoke about the need to use non-fixed hours contracts because of the flexibility demanded by the organisation to respond to changes in contracts and to fit around the personal needs of the client (such as dealing with cancelled hours if the client goes on holiday or has an unexpected hospital admission). This can lead to very long days with unpaid ‘down time’ in the middle of the day and unpredictable schedules.

Disparities between contacted and actual working hours not only affect care workers’ direct pay, but can also impact negatively on entitlement to sick pay and holiday pay. Contractual variability can also undermine their integration into their teams and opportunities for learning and development.

“It’s helped me a lot to learn, because when I was just like relief, you were just coming and doing the basics and that but now I’ve got the contract you actually feel you’re somebody. I feel quite important actually, you know… all the different stages of learning that I’m doing.”

Source: Scottish Social Services Workforce 2017 Data

Employers in the care sector face scarce (mainly public) resources and commissioning arrangements are often beyond employer influence or control. Stable, long-term and sufficient funding for the care sector is required to underpin a secure employment environment for care workers. But there is also a need for better organisation-level management of demand to deliver fair work, where contracts more closely reflect hours actually worked and where there is more and better planning to provide more predictability in work rotas and scheduling.

Opportunity

Fair work is work that is open to all without discrimination and which embeds training, learning and career development, thus supporting social mobility. Key questions for the sector, therefore, related to opportunities for training and career development.

Care workers interviewed for the research were often very positive about the learning and training on offer from employers. Care workers spoke about the extensive training on both care delivery and broader organisational skills, such as shift organisation. They also spoke about the necessity to undertake vocational training and of the considerable investments (time and money) being made in training to meet SSSC registration requirements.

The SCER research identified examples of fair work practice, with employers offering a range of training and e-learning options. However, there was some evidence from participants that work pressures could mean that staff struggled to balance work and learning commitments. Understaffing, caused by recruitment and absence problems was seen by some care workers as a barrier to their own learning. There was also evidence that work pressures could mean that staff struggled to balance work and learning commitments.

“You’re having to do your SVQs, and then there’s all this learning, there’s just so much getting piled on…you’re staying up that bit later at night to get it done.”

Source: The Labour Force Survey 2017, ONS

There were also examples of workers being involved in a variety of specialist tasks.

“I’ve learned an awful lot since I’ve been here in the dementia unit. I’ve been doing as much studying as I can, so I can enhance my role. I’m doing an enhanced dementia course now, so I can do the job better and understand… It’s not just about the person with dementia, it’s the whole family and their friends that feel it too, and you want to give them support. And day-to-day care and everything.”

The SCER research found only a minority of workers felt that most or all colleagues’ skills were used effectively, which adds to existing evidence that skills under-utilisation might be a problem. Only two-fifths of employees surveyed reported that, for most or all or their colleagues, their employer developed people’s skills for the future as well as the present or that their employer used people’s skills and talents effectively. This suggests significant untapped potential within this workforce but also raises a question about the suitability and relevance of the training provided.

While care leaders highlighted some interesting examples of groups of smaller independent organisations collaborating to share the costs of running training, there remains a need to maintain and share existing good practice on training and development in the sector, while seeking to ensure that staffing and other resources are in place, so that care workers can balance work and learning commitments. There is also a need for sufficient resources to assist care organisations to fully resource both training and time off for training. It is important that care organisations have the resources to help to free up staff time and reduce pressures associated with losing staff to training.

Most care workers in the survey were keen to continue in the sector but did not know how their career would progress, perceiving that opportunities for progression were limited. Some leaders acknowledged the challenge associated with encouraging staff to see social care as a career. There may be benefits in strengthening practice-sharing in career planning and development, as well as in identifying how organisations can articulate the range of specific skillsets and roles required by the sector and support staff to progress towards those roles.

Effective voice

Fair work requires that organisations have practices allowing for employees’ views to be sought out and for employees to be listened to, to influence and to be able to make a difference. Key questions focused on the presence of trade unions; whether care workers had opportunities to use their voice and contribute their ideas; and specifically whether opportunities existed to engage in co-producing personalised care in collaboration with services users?

In a social care context, care workers’ views and voice are particularly important at a time when they are being challenged to co-produce personalised care in collaboration with service users. However, opportunities for contributing to decisions and effecting change were limited according to many care workers participating in the research.

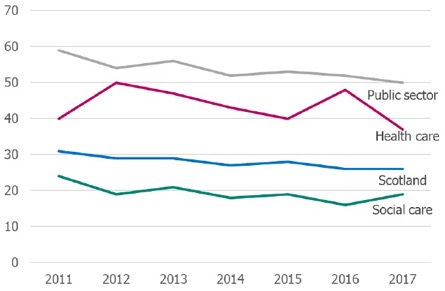

Figure 6: Percentage of workers in workplaces where agreements with trade union affect pay & conditions

Source: Labour Force Survey, ONS

Only three in ten care workers in the SCER survey agreed that most or all employees had a strong collective voice. Only a minority thought their organisations actively sought to negotiate changes in pay and conditions with employees, or that employees had an active role in the introduction of new ways of working. While both care workers and leadership team members acknowledged a range of strategies for employee voice within care providers, there was sometimes a sense that opportunities for staff to be ‘heard’ and influence management decision-making were limited.

Leadership teams acknowledged that there was a constant need to invest in and maintain relationships between employees and trade unions:

“We work in very close partnership with UNISON. They are driving the Fair Work Framework in terms of working practices in terms of terms and conditions and rights of workers, so everything that we do is hopefully for the benefit of the people that work for us.”

Interviewees acknowledged that there were challenges in ensuring employees could feedback ideas and concerns on a day-to-day basis, given the dispersed nature of the workforce and heavy workloads.

Workers criticised some of the practices of their organisations: sometimes mechanisms were seen as one-sided and about imparting information, rather than about consulting and engaging the workforce.

There is a need to ensure that employee voice mechanisms engage with a workforce that is often dispersed and faces considerable work demands; and it is important that, where trade unions represent care workers, there is the fullest possible dialogue and partnership with employers.

Fulfilment

The Fair Work Framework highlights that “fulfilling work can be an important source of job satisfaction individually and collectively” and it is often rooted in the opportunities to learn, to use talents and skills, to engage in challenging activities, to solve problems, to take responsibilities and to make decisions. Key questions, therefore, focused on whether jobs were felt to be meaningful and aligned with the workers values; the pace of work and work pressures; autonomy and monitoring; and the role of supervision and support.

Among survey respondents, 71% thought that their workplace provided jobs that are meaningful. More than three-quarters described themselves as satisfied or very satisfied in their work. More than four-fifths of workers in the SCER research agreed that sharing the values of their care organisation was an important personal motivator.

When asked about the best feature of their work, care workers referred to specific examples of fulfilment linked to feeling that they had delivered excellent care for service users.

“I work in supported living accommodation with six adults, all completely different. And basically, we support them to have a normal life. It’s so very rewarding… It’s a really good job, really good.”

“It’s nice to be involved in people’s lives and to walk away at the end of the day thinking you have made a positive difference.”

“All the people [service users] praise me for what a good job I did and that just made me feel like I was right up there. That was such a good feeling, to know that I am appreciated.”

Care workers gain considerable self-worth from the sense that their work was valuable and that they were making a difference to service users’ lives. Yet there was an acknowledgment in some of the SCER interviews that work pressures, especially having insufficient time to engage with service users, could undermine feelings of fulfilment. The stress involved in having to curtail time with service users can undermine their sense of meaning and fulfilment and may impact negatively on care workers’ wellbeing.

“We’re a bit short-staffed. It’s been that people have found other jobs or are on maternity leave or are on holiday. You find yourselves very poorly staffed, and it is really difficult… I can’t remember the last time we had too many staff, or even the right number. Sometimes you’re so busy trying to get things done for them that you don’t have time to speak with them (service users), or just take an interest in them.”

Much of the care delivered by most of the participating organisations was based on commissioning that allocates a set number of hours of care. This approach to delivering defined by hours of care sometimes contributed to a sense of frustration, undermining the fulfilment of care workers who were concerned that they were not spending enough time with service users:

“Some folk only get allocated a certain amount of time and we go in and say ‘we can’t possibly do it in that time’, and we’re running over our time with them. We’ll keep phoning and saying that ‘they need more time’, so (our team leader) phones social work, and hopefully it gets allocated. If we don’t say anything, it won’t get changed. Other service users get upset because they think you have forgotten about them and it can take the rest of the day to catch up.”

Previous research has suggested that these models of care provision can be stressful for care workers, who are sometimes required to rush between times appointments.[32]

“We did have a home care contract, a large home care contract which we don’t have anymore, and that involved call monitoring by the minute, so we were getting paid literally by the minute. That wasn’t fair to colleagues, because of pressure that they were under. It’s not helping someone live a valued life.”

The contracts and therefore the type of care work delivered by organisations may have the potential to constrain care workers’ experiences of fulfilment. However, some care workers gave examples of having substantial autonomy to shape their work to service users’ needs and took considerable joy in drawing from their own abilities and interests, as well as having the capacity and autonomy to connect with service users’ needs and interests.

The intrinsic value of care work matters, as finding meaning helps care workers to cope with the pressures associated with the challenging nature of the job. However, these same coping mechanisms can normalise and legitimise overwork and burnout, bringing risks of self-exploitation among care workers that may undermine their wellbeing.[33]

During research with the independent sector, some care leaders spoke about the increasing use of electronic monitoring, which meant that any time programmed not spent with service users was deducted from payments to the provider. This practice intensified pressure on staff to arrive and leave at exact times, rather than being able to respond flexibly. Reflecting on these issues, many organisational leaders and managers argued for a model of commissioning that focused on outcomes and wellbeing, rather than hours of care, as being important to ensuring fulfilment elements of care work.

“What we want to do is commission on outcomes so… then the whole point is that you’ve got this upskilled workforce that can work with that individual and look at creative ways of meeting those outcomes for that person without saying ‘it needs to be done within 15 hours a week’ or whatever it is.”

“It’s a commitment-based job, but the organisation of work is being done through ‘time and task’.”

The SCER survey research and interviews found that care workers valued supervision as a source of support and an opportunity to reflect on practice. This was seen as particularly important given the challenging nature of care work particularly for those who experience long periods of lone working. Concerns were raised regarding the pressures in undertaking complex and emotionally challenging work, with one in ten care workers reporting that their colleagues experienced a sense of isolation.

There were some concerns among survey respondents about the time and resources available for regular supervision. While most care workers are positive about the supervision they received, some concerns were raised that time pressures meant that supervision sessions were sometimes not able to explore career development or how well employees were coping.

“What makes this sector really different, I think, is that the level of responsibility… I mean, it can be life and death… I feel that as a responsible employer we have a duty of care… There’s a lot of lone working as well… so for us, it’s really important that those supervisions take place, and they have team meetings and that staff feel part of something.”

Supervision and support is important to the delivery of fulfilling work in the social care sector. Yet supervision is perhaps easier to reduce as a cost than front line service delivery. Given its importance, however, the need to resource and support supervision should be ‘locked in’ to considerations of funding and commissioning. Funders, key stakeholders and care organisations should work together to ensure that high-quality supervision is fully costed and supported in contracts to deliver care. There may be value in further research on what best practice in supervision looks like and identify a unit cost that can be incorporated into contracts.

Respect

The Fair Work Framework document notes that “respect involves recognising others as dignified human beings and recognising their standing and personal worth”, consistent with international Human Rights obligations in relation to just and favourable conditions of work.[34]

The issue of respect spans respect for health and well-being, for family life, for status and for contribution. Crucial questions focused on whether social care as a profession is respected by society; whether workers feel respected by their colleagues and their employers; and whether work-life balance was respected.

Findings on the respect dimension of Fair Work were broadly positive. Most of the survey respondents (72%) thought that colleagues treated each other with respect and reported high levels of job satisfaction. Survey respondents were also broadly positive that their organisation would deal with bullying effectively and were able to identify fair work practices promoting respect and combating inappropriate behaviour.

However, most of the survey respondents also identified problems of stress and overwork among colleagues. Interviewees spoke of the pressures associated with having to cover colleagues as a result of absence or staffing shortages. Although interviewees reported a range of fair work practices in the form of wellbeing interventions, there were significant concerns around stress and overwork.

The vast majority of respondents thought that at least some colleagues found work stressful; with almost half reporting that most or all employees experience stress. In addition, two-fifths of respondents thought that most or all of their colleagues were overworked. This corresponds with national statistics for the sector.

In interviews, care workers described a range of factors contributing to stress: the demanding nature of care work, the desire of care workers to do their job well, the (sometimes) limited time available to deliver care, and (in some cases) understaffing and the need to take on additional hours for financial reasons, both of which fed into overwork.

“The weekends are more stressful, because obviously you’ve got less staff… if someone phones in sick on a Thursday (team leaders) have to still get cover, and make sure everybody still gets their care. Sometimes pushing people in to cover, that can be stressful.”

There was a sense that sporadic experiences of overwork and tiredness were accepted as ‘part of the job’.

“There’s always extra hours going, because there’s always someone phoning in sick, or an extra care package that they need ASAP. There’s loads of overtime if you want it. Sometimes too much! I’m on a zero hour’s contract… I’ve got no complaints, just that sometimes it’s a long day.”

“I ask for 20 [hours]. They were very short-staffed for a while and some weeks I was doing 30, 32, 37 in one week.”

Some workers delivering care at home services described the stress involved in their constant worry about running late during their run of home visits. Given their workload, their reliance on colleagues to deliver care, and the complexity of the services being provided, the risk of running late loomed large in some care workers’ minds and was a significant source of stress and worry.

Source: The Labour Force Survey 2017, ONS

Care workers thought that many of their colleagues experienced stress and overwork and told of how their commitment to service users would often result in workers accepting additional hours. This chimes with national statistics showing that, in 2017, 27% of Scotland’s female social care workforce worked for over 41 hours a week (including overtime) and an additional 11% of the female care workforce worked for over 50 hours weekly.[35]

Many of the dimensions of Fair Work are connected in the social care sector. How care is seen by outsiders – as a low paying sector – feeds into recruitment and retention problems that impact other dimensions of Fair Work: from opportunities to access supervision and training, to the opportunity to gain fulfilment from work. Staffing problems and work intensification may also directly impact negatively on the wellbeing of some workers.